The Balfour Centennial—A Time of Reflection & Introspection

November 2, 2017 marks the 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration. But past anniversaries of this moment have been controversial, and the centennial is proving to be no exception.

In 1917, at the height of World War I but with an eye to the new world order that would come at the war’s end, the British Foreign Office issued a proclamation to the English Zionist leadership: “His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people…” With the tacit support of the U.S., Russia, France, Italy, and even the Vatican, the British offered the first international political recognition of the Zionist movement that had been catalyzed by Theodor Herzl and the First Zionist Congress twenty years earlier.

But should we care? From a certain Zionist perspective, celebrating Balfour is the epitome of “golus mentality” (i.e., thinking like you’re still in the ghetto). In other words, why should Jews need foreign validation for their own liberation movement? Zionism was supposed to free us from that sort of thinking!

And from an anti-Zionist perspective, Balfour was cynical to say the least. Zionist opponents like MP Edwin Montagu, the only Jew in the British cabinet in 1917, insisted that a Jew who longed for Zion had “admitted that he is unfit for a share in public life in Great Britain, or to be treated as an Englishman.” This idea, that Jews in emancipated Western Europe and America had left Exile behind for modern Promised Lands, was already passé by 1917, but it endured in many entrenched Jewish establishments.

But to understand what Balfour meant to those who celebrated Jewish peoplehood—and Zionism was, first and foremost, an acknowledgment that there were national ties that bound Jews around the world to one another—we can find a profound illustration in the books of Rabbi Chaim Hirschensohn (1857-1935).

Hirschensohn was an Orthodox rabbi, born in Safed and raised in Jerusalem. He cultivated a friendship with the fervently secular and nationalistic Eliezer ben Yehuda, the key proponent of Hebrew as a modern, living language of the Jewish nation. For his efforts—and in a dark foreshadowing of today—Hirschensohn was excommunicated by the Orthodox rabbinate in Jerusalem for daring to propose that halakha and modernity could co-exist. He left Palestine in 1901, never to return. He landed in, of all places, Hoboken, New Jersey, where he spent the rest of his life.

Hirschensohn never relinquished his belief in Zionism or his dedication to the Jewish people. He composed, among other books, a multi-volume work called Malki Bakodesh, which analyzed modern questions (such as women’s suffrage) through the lens of halakha. And on the title page of Malki Bakodesh, beneath the biblical epigrams, is the date of publication. It reads :

5679 [= 1919]

The Second Year since the recognition of the British Kingdom

to our right in the Land of Israel

In other words, Hirschensohn was embracing two timelines. 5679, in the traditional Jewish counting. And—Year 2, since the Jewish nation leapt back into history!

That is the profound meaning of Balfour. For people like Hirschensohn, watching events unfold from New Jersey with his heart in Jerusalem, time was starting anew. And Jews around the world, for whom the luster of modernity had tarnished with the devastation of World War I and the sadism of pogroms in Eastern Europe, saw themselves validated as a legitimate people with a past and a future.

Since then, the anniversary of the Balfour Declaration has been marked with peaks of joy and valleys of disinterest.

On the 10th anniversary, Zionist leader Berl Katznelson was (already!) scolding the halutzim for forgetting their history. The anniversary was passing virtually unnoticed. In an editorial in Davar, in the preeminent newspaper of the Yishuv, Katznelson argued: “On this day, a day of memory and reckoning, those at the helm should stand proudly and count everything that has been done and achieved.… They will learn how to accept the days of the future, if they be difficult, with mental fortitude and courage.”

On the 25th anniversary, the Jewish world was a more sober place. Knowing full well of the Nazi atrocities that were occurring, David Ben Gurion reminded the nation that the anniversary of Balfour was not a celebration—but a solemn reminder of precisely why Jewish autonomy was a necessity.

Subsequent anniversaries of Balfour were often completely neglected, due to a variety of factors. These include the priorities of building the State—but also a considered ambivalence about the British, who subsequent to Balfour had often opposed Jewish expansion in the land.

On the 50th anniversary, less than five months after the victory of the Six Day War, Israelis were ready to embrace their past—and the legitimacy that it bestowed in the community of nations. The headiness of those days promised that peace and normalization were at hand. And that was a process that had been sparked by Balfour.

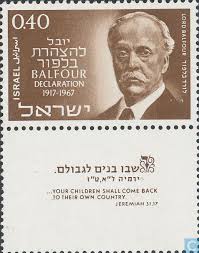

So postage stamps were issued of Lord Balfour and the Declaration’s architect, Chaim Weizmann. Each stamp carried not only an image of the man, but also a biblical reference. Balfour’s portrait was enhanced by Jeremiah 31:17, translated in this way: “Your children shall come back to their own country.” Weizmann’s picture included the word yovel, the biblical Jubilee, when ancient Israel was commanded to “proclaim liberty throughout the land for all its inhabitants.” That is to say, Israel was the latest chapter of the ancient saga of the Jewish people—interrupted by a 2000-year exile.

Today's centennial brings out all these complexities. In 2016, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas in a U.N. called for the British to mark the anniversary with “an apology to the Palestinian people for the catastrophes, miseries, and injustices that it created.” British Prime Minister Theresa May, to her great credit, will ignore that call and celebrate the milestone with Prime Minister Netanyahu in London. (UK Labour Leader Jeremy Corbyn, who has a problem with confronting antisemitism in his party, announced that he would not be attending the celebrations.)

For the rest of us, this centennial could be a time for reflection about the meaning of Israel in our lives. We live in an extraordinary generation in Jewish history: a generation that knows a state of Israel. And the Balfour Declaration was a key moment in bringing that remarkable reality to fruition.

On the other hand, Jewish peoplehood is being torn and tattered by its leaders. The Prime Minister of Israel has proven himself to be an adversary to the unity of the Jewish people, by creating a cabinet of reactionary zealots and jettisoning large swaths of the world’s Jews for the sake of holding on to political power. The crisis at the Western Wall—in which the government forged a remarkable compromise and then abandoned it after pressure from the ultra-Orthodox parties—is a symbolic illustration of this behavior. American Zionist leadership has shown itself to be unwilling or unable push the issue of religious pluralism in Israel as a fundamental priority.

There is much to be worried about in regard to Israel’s future. But milestone anniversaries such as this one—a forshpeis to the 70th anniversary celebration of Israel’s Independence next May—remind us of the incredible story that is modern Israel.

And it should compel each of us to explore our own responsibilities to make sure that Israel remains true to its founding principles, to be a democratic “national home” to every Jew.