Elegy for… a Character: A Tzedakah Story

Even a poor person—one who is sustained by Tzedakah funds—

is required to give Tzedakah to another person.

Maimonides, Mishneh Torah

Laws of Giving to Poor People 10:5

My friend Renee was a character. She was well known in our town; you couldn’t miss her. Her frizzy salt-and-pepper hair was often bound in a pigtail like a schoolgirl’s. She drove an SUV that was constantly breaking down, packed to the roof with the telltale possessions of an inveterate hoarder. She had weary eyes that conveyed years of adventures.

She lived on the precipice of homelessness. For a while she stayed in emergency shelters—scary places that she would recount with stark tales. In recent years, she found more stable housing, finding cheap rooms to rent in residential homes around Natick. And she knew how to work the system, making her rounds to get the food, gas money, and, especially, the money for medications that she needed.

I suppose that’s where I came in. She started dropping in on me years ago at the synagogue where I worked. At first she came for Tzedakah money, knowing that people gave me funds to distribute in emergency situations. But she would linger, telling me stories, asking about my family, and, I think, looking for some human contact that can be the harshest thing people who are very poor lack.

Like many such characters, she tested the nerves of those who didn’t “get” her. When she began to show up at the synagogue—ensconced in one of the wealthiest Zip Codes in America—some people whispered behind her back. Being Jewish herself, she accepted my invitation to come to Friday night services. Sometimes the bar/bat mitzvah families with out-of-town guests would murmur about the woman who looked funny and took too much of the food that was offered before the service began. The staff grumbled when she would sit on the couch outside my office, waiting without an appointment to grab a few minutes of my time. Hebrew school parents and kids kept their distance.

She was funky. She looked funky, she talked funky, and sometimes she smelled funky. Initially our relationship was based on shnorring—she needed money, and she knew that I was usually reliable to help her pay her heating bill during the cold winter, or fill a prescription for her urgently-needed heart medicine.

Sometimes she exasperated me. I know, of course, about the social service agencies in our area that are there to provide a safety net. I begged her—I insisted—that she connect with them. She would reply that her nonconformist hippie soul wouldn’t be part of their “system.” That made me crazy; I threatened to cut her off if she didn’t take their assistance. But she would inevitably show up with a bill for heart medication, and of course I would help pay for it.

After a while, the dynamic of our relationship changed. She knew I was going through some rough times personally, so one day she invited me to lunch. I demurred—where in the world would she get the money from?—but she insisted. So a few days later, she took me out to a local diner. I’m sure we got a few stares. But the gesture meant so much to me: she considered me a friend; she knew I was down, and she treated. She didn’t even let me cover the tip.

Yes, she was a character. She wasn’t invisible, but she became one of those offbeat folk who populate a suburban town who are tolerated as long as they don’t become too much of a nuisance.

But because she was my friend, I knew things that others didn’t.

I knew that she had a Master’s degree in counseling from the University of Wisconsin. I knew about her daughter at American University, of whom she was very proud. I knew that she had spent time in Israel, and spoke a limited but comprehensible Hebrew. And I knew she still saw herself as a “Sixties Person”—committed to volunteerism and social activism. She once told me stories about working on the Clearwater Project on the Hudson River with Pete and Toshi Seeger.

But now I’ll share something with you that very few people knew (including her daughter, until I told her). She couldn’t stand just being on the receiving end of the cycle of caring. “This isn’t me,” she’d say, insisting that her younger self was alive and well inside her rather emaciated and graying body.

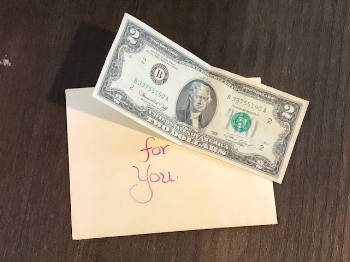

So one day she handed me a large folder. “I know you see a lot of hurting folks throughout the course of the day,” she said. “So when you feel it’s appropriate, please give people one of these.”

Inside the folder were ten envelopes labeled “For You.” In each one was a handwritten personalized note. Each was a gentle message of compassion and tenderness. For instance:

To remind you

How unique and

Wonderful You

Are—

every day,

every hour

—And to wish you

extra energy for the things you’re

currently tackling…

Or:

Please accept this

as a symbol

of some

great things

comin’ your way—

for example

Brightness

Fairness

HAPPINESS…

Enjoy your

wonderful

future.

And enclosed in each card was a $2 bill. (A $2 bill!) The instructions were not to keep this money for yourself, but to take it and use it to brighten someone else’s day.

Look at what an extraordinary Mitzvah that is. She did it completely anonymously; she left it to me to identify the adults, teens, or kids who needed cheering-up. I was not to tell the recipients where it came from; it was just from “a friend, someone who cares.” And the cards were designed to trigger a chain reaction of compassion and human kindness. This is Tzedakah—but Tzedakah with the personal touch, rooted in compassion and a desire to make a connection with people who may be desperately lonely.

Renee died last week; her heart finally gave out, surely not helped by the on-the-edge lifestyle she was living. There weren’t obituaries in the paper or online; few people noticed. Many who encountered her over the years may have forgotten her, or figured that she just skipped town. But she deserves a better memorial.

I know many more juicy stories that she shared with me, but I won’t tell them here. Suffice to say that she was a character, and she lived out the Rambam’s principle that everyone’s (everyone’s) task is to bring kindness and caring into the world, not indifference and lies. I just wanted to say that she was my friend, I’ll miss her, and she made a difference.